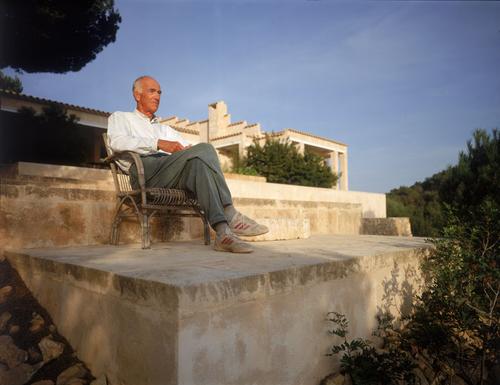

“I like to be at the edge of what is possible” said Jørn Utzon while he sat to contemplate the view from the terrace of his house in Marbella.

“I like to be at the edge of what is possible” said Jørn Utzon while he sat to contemplate the view from the terrace of his house in Marbella.

Utzon (1918-2008), architect, did just twenty something projects through his career, 7 or 8 drawings and one article, he is one of those great talents who has managed to go undetected/unseen through life.

When Swedish architect Gunnar Asplund was dying (he died out of stress), he asked his son, if all that effort through his professional life was worth it at the end of his days… This words were really present in Jørn Utzon mind when, after nine years working on the design and construction of his winning project for the Sidney Opera, decided to resign in 1966 for the lack of professional respect he was getting by the Minister of Public Works. And in 1972 he retires almost completely from Architecture and built his house (cornerstone to understand his work and sensibility) in Mallorca.

But here we are not going to analyze Can Lis, his beautiful Mallorca house, but one of his unbuilt projects which is also amazing and so advanced for his time, the 1967 Stadium and Sports Complex competition for Jeddah (Saudi Arabia).

“we are not really interested in how things will be in 25 years, whatever we build. actually, what we are interested in is that if in 2000 years some people dig down, they will find something from a period with a certain strength and purity belonging to that period” -Utzon, 1978.

The Jeddah Sports Complex is one of the most beautiful projects by Utzon. A commission he won by way of Kenzo Tange and which sadly remained unbuilt until today. And this work shows Utzon’s forward thinking and his sensibility using as a resource the development of folded construction and system thinking of which we see plenty these days, that’s why we think the Jeddah project deserves to be remembered.

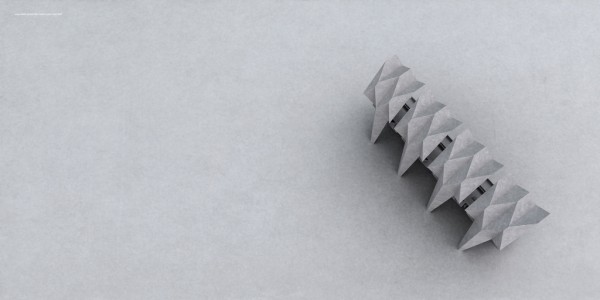

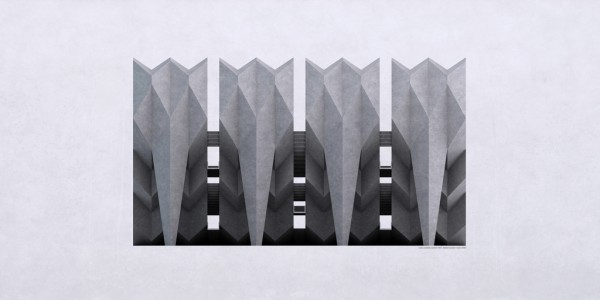

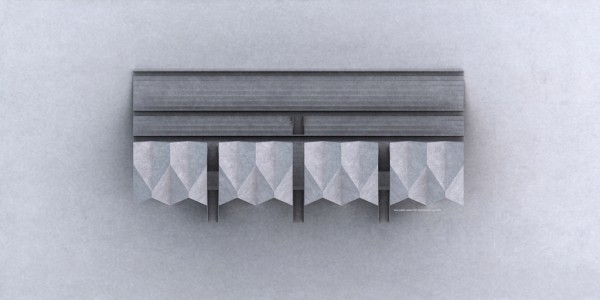

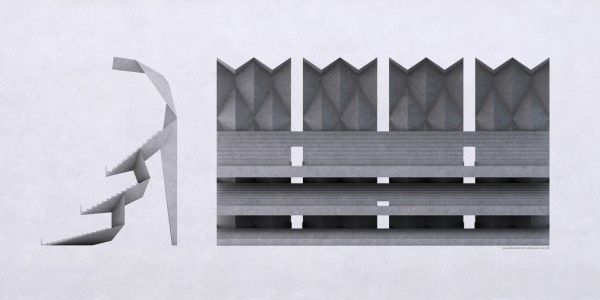

Due to the lack of documentation for this post we supported on the research & images of a digital model produced by SEIER+SEIER which are based on the drawings published by Jørn Utzon in Danish magazine “arkitektur” #1 in 1970, an issue devoted entirely to Utzon’s concept of additive architecture which proposed open-ended building systems of almost organic growth, yet consisting of a limited number of prefabricated units.

This rendering shows four such modules for the stadium grandstand. we know few details, hence the high level of abstraction, but in his later works Utzon increasingly eschewed details for the naked presence of his monumental concrete structures.

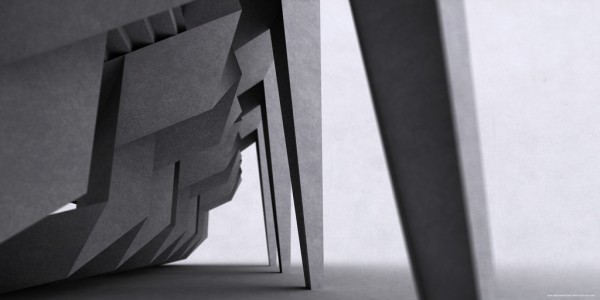

Utzon, in his own text on the Jeddah stadium stresses the rationality of prefabrication and how the additive architecture supports the natural flow of people through the complex. Still in this very same text, we feel that Utzon was trying to divert the attention from his best tricks in the project: imagine to stand next to such captivating shapes in the thinnest possible folded concrete… would your thoughts wonder about rational production and patterns of movement?

Folded plate constructions in concrete are not in themselves unusual for the late sixties. What is exceptional is Utzon’s ability to invest it with layers of meaning without adding physically to the minimal structure. In the context of the Arabian peninsula, the faceted concrete resembles the Islamic Muqarnas vaulting, Utzon had witnessed in Isfahan and the many prismatic derivatives found in that most beautiful of cities. but it is no mere allusion to one of Islamic architecture’s most iconic elements. Utzon lifts it from role as ornament into modern construction, returning it to the constructive purity of its origin, the squinch. That cultural continuity was possible within modernism and the conditions of the 20th century is one of the salient points of Jørn Utzon’s work regarded as a whole. One can only hope that the people responsible for the ongoing embarrassment which is historicist Islamic architecture today will look to him for guidance.

To the Danish eye, the relationship to the cross-pleated paper lamps of the Klint family is the most immediately intriguing. Former employees testify to Utzon’s admiration for p.v. Jensen-Klint’s Ruskinian monument, the Grundtvig church, and for his son, Kaare Klint, the uncompromising father figure of Danish furniture design. In effect, they were the true royalty of the Copenhagen scene. The le klint lamps were put into production by his sons some forty years after p.v. Jensen-Klint invented the first version for his own home. still developed and reinterpreted by new generations of architects, it remains one of the true classics of danish design – but why did it turn up, violently out of scale, in Utzon’s oeuvre?

In a rare bookshop find, we had the chance to encounter the memoirs of Le Klint, Jensen-Klint’s grand-daughter after whom the company was named. of her stay in neutral sweden in 1944 she writes:

“…Jørn Utzon…lived under the roof in one of Gamla Stan’s beautiful flats. his wife received me…Jørn arrived home from work and was wildly enthusiastic about the lamps – especially Kaare’s lamps which he hung all across the little flat.”.

and later,

“Jørn immediately set about planning the exhibition. in the evening we would sit all three of us making new lamp shades until long into the night. the exhibition room was large and several hundred lamps were needed.”

You can only imagine how he must have stored the idea for using folded construction on a larger scale. the first place it turned up in his production was an early idea for the inner acoustic shells of the Sydney opera house – a beautiful, triangulated surface but less repetitive and more complex than the Saudi project.

For all his universal aspirations, maybe this autobiographical trait in Utzon’s works as each project seems to draw up world maps of his encounters and personal experiences is the most interesting. It is the very opposite of the architecture coming out of the major offices that undertake projects on this scale today.

Some of the design ideas behind the Jeddah Stadium were later recycled by Renzo Piano in Bari, and others by Santiago Calatrava just about everywhere.

great architecte really